24-hour sleeplessness ( non-24 ), is one of several sleep disorders of chronic circadian rhythm (CRSD). This is defined as "a chronic stable pattern consisting of [...] daily delays in sleep onset and waking time in individuals living in society." Symptoms occur when a non-entrained endogenous circadian rhythm exits from harmony with a light/dark cycle in nature.

Sleep patterns can vary greatly. People with a circadian rhythm that is close enough to 24 hours may be able to sleep with a socially acceptable conventional schedule, ie at night. Others, with "daily" cycles upwards of 25 hours or more may need to adopt sleep patterns that are in harmony with their free-running circadian clock, shifting their sleep time each day, so often get satisfactory sleep but suffer social and work consequences.

The majority of people with non-24 are completely blind, and entrainment failure is explained by the absence of photic input to the circadian clock. These people's brains may have a normal "body clock," but the clock does not receive input from the eye about the level of ambient light, since the clock requires a functioning retina, optic nerve, and visual processing center.

This disorder also occurs in people who are seen for reasons that are not well understood. Their circadian rhythms are abnormal, often running for more than 25 hours. Their visual systems can function normally but their brains are not able to make major adjustments to the 24 hour schedule.

Although commonly referred to as non-24, for example by the FDA, the disorder is also known by the following terms:

- 24-hour sleep-wake syndrome

- 24-hour sleep-wake disorder

- 24-hour sleep-wake rhythm disturbance

- free running error (FRD)

- Hypernychthemeral Disorder

- Sleep disordered circadian rhythm - the type of free running

- Sleep disordered circadian rhythm - untrained type

- N24HSWD

- Non-24 hour circadian rhythm disturbance

The disturbance in its extreme form is an invisible disability that can be "very debilitating because it does not fit most social and professional obligations".

Video Non-24-hour sleep-wake disorder

Karakteristik

Sighted

In people with non-24s, the body basically insists that the length of a day (and night) is long (or, very rarely, shorter) than 24 hours and refuses to adjust to external dark-duty cycles. This makes it impossible to sleep at a normal time and also causes daily shifts in other aspects of circadian rhythms such as peak standby time, minimum body temperature, metabolism and hormone secretion. A 24-hour sleep-wake disorder causes a person's sleep-wake cycle to move at all times of the day, to a degree depending on the length of the cycle, finally returning to "normal" for a day or two before "going" again. This is known as sleeping freely.

People with this disorder may have a very difficult time adjusting to changes in the "usual" sleep-wake cycle, such as vacations, stress, night activities, time changes such as summer time, trips to different time zones, illness, (especially stimulants or sedatives), daytime changes in different seasons, and growth bursts, which are usually known to cause fatigue. They also showed a lower sleeping tendency after a total sleep less than normal sleep.

Non-24 can start at any age, not infrequently in childhood. Sometimes it is preceded by delayed sleep phase disorder.

Most people with this disorder find that it severely damages their ability to function in school, in their work, and in their social life. Usually, they "part or all of them can not function in daily scheduled activities, and most can not work on conventional work". Attempts to maintain conventional hours by people with disorders generally result in insomnia (which is not a normal feature of the disorder itself) and excessive drowsiness, to the point of falling into microsleeps, as well as the various effects associated with acute and chronic sleep deprivation.. Seeing people with non-24s who force themselves to live on a normal business day "is not often successful and can develop physical and psychological complaints during waking hours, ie drowsiness, fatigue, headache, decreased appetite, or depressed mood. have difficulty maintaining regular social life, and some of them lost their jobs or failed to attend school. "

Blind

It is estimated that non-24 occurs in more than half of all people who are totally blind. This disorder can occur at any age, from birth and beyond. Usually occurs immediately after the loss or removal of a person's eye, because the photosensitive ganglion cell in the retina is also removed.

Without light to the retina, the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN), located in the hypothalamus, is not synchronized daily to sync circadian rhythms to a 24-hour social day, producing non-24 for many individuals who are totally blind. Non-24 is rare in patients with visual impairment who have at least some perception of light. Researchers have found that minimal nighttime light exposure can affect body clocks.

Maps Non-24-hour sleep-wake disorder

Symptoms

Symptoms reported by patients imposed on a 24-hour schedule are similar to those that lack sleep and may include:

Cause

Sighted

People seen with non-24 appear to be rarer than the blind with the disorder and etiology of their circadian disorders are poorly understood. At least one case of people seen experiencing non-24 was preceded by a head injury; another patient diagnosed with the disorder was later found to have "a large pituitary adenoma involving optical chiasm". Thus the problem seems to be neurological. In particular, it is thought to involve the abnormal function of the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) in the hypothalamus. Several other cases have been preceded by chronotherapy, a prescribed treatment for delayed sleep phase disorder. "Studies in animals show that hypernyctohemeral syndrome can occur as a physiological side effect prolonging the sleep-wake cycle by chronotherapy". According to the American Academy of Sleep Medicine (AASM): "Patients with free-running rhythm (FRD) are thought to reflect entrainment failure".

There have been several experimental studies on people with visual impairment. McArthur et al. reported treating patients seen as "becoming subsensitive to bright light". In other words, the brain (or retina) does not react normally to light (people with disorders may or may not, however, be extraordinarily subjective subjects sensitive to light, one study found that they are more sensitive from the control group.) In 2002 Uchiyama et al. examined five non-24 visible patients who showed, during the study, an average sleep-wake cycle of 25.12 hours. That's pretty much longer than the average 24.02 hours shown by the control subjects in the study, which are close to the average congenital cycle for healthy adults of all ages: 24.18 hours discovered by Charles Czeisler. Literature usually refers to "one to two hours" delays per 24 hours a day (ie 25 to 26 hour cycles).

Uchiyama et al. had previously determined that the minimum core temperature of 24 patients visible was seen much earlier in the sleep episode than two hours before waking. They suggest that long intervals between ambient through and waking temperatures make illumination on waking almost ineffective, corresponding to the phase response curve (PRC) for light.

In their clinical review in 2007, Okawa and Uchiyama reported that people with Non-24 had a median duration of nine to ten hours and that their circadian period averaged 24.8 hours.

Blind

As stated above, the majority of patients with Non-24 are completely blind, and the failure of entrainment is explained by the loss of photographic input to circadian clocks. Non-24 is rare in patients with visual impairment who have at least some perception of light; even minimal exposure to light can synchronize the body clock. Some cases have been described where patients are subjectively blind, but are usually entrained and have an intact response to the effects of pressing light on melatonin secretion, suggesting a preserved nerve path between the retina and the hypothalamus.

Mechanism

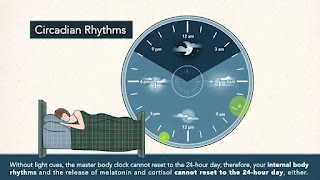

Internal circadian clocks, located in the hypothalamus of the brain, produce signals that are usually slightly longer (sometimes shorter) than 24 hours, averaging 24 hours and 11 minutes. This small deviation, in almost everyone, is corrected by exposure to environmental time cues, especially the dark-light cycle, which rearranges the clock and synchronizes to 24-hour day. The morning light exposure resets the previous clock, and the afternoon exposure resets the hours later, thus grouping the rhythm to an average 24-hour period. If normal people lose external time cues (live in caves or artificial insulated time-environments without light), their circadian rhythms will "walk free" with fewer cycles (sometimes less) than 24 hours, expressing the intrinsic period of every circadian clock individual. The circadian rhythms of individuals with non-24 can resemble experimental subjects living in isolated environments of time, even though they live in normal societies.

The circadian clock modulates many physiological rhythms. The most easily observed is the tendency to sleep and wake up; thus, people with non-24 symptoms experience insomnia and daytime sleepiness (similar to "jet lag") when their endogenous circadian rhythms come out of sync with a 24-hour day of social/solar and they try to adjust to schedule conventional. Finally, their circadian rhythms will return to normal alignment, and symptoms will be temporarily lost, but then their clocks float out of alignment again. Thus the whole pattern involves recurring symptoms every week or every month, depending on the length of the internal circadian cycle. For example, an individual with a 24.5 hour circadian period will drift 30 minutes later every day and will be maximal out of every 48 days. If patients set their own schedule for sleep and wake, in line with their endogenous non-24 period (as is the case for patients with this disorder), the symptoms of insomnia and sleepiness wake up considerably. However, such a schedule does not fit most work and social relationships.

Diagnosis

Sighted

Diagnosis is usually made based on a continuous delayed onset of sleep history following a non-24-hour pattern. In their big series, Hayakawa reported the average day length is 24.9 Ã, Â ± 0.4 hours (range 24.4 to 26.5). There may be evidence of "relative coordination" with sleep schedules becoming more normal as it coincides with conventional time to sleep. Most reported cases have documented a non-24 hour sleep schedule with a sleep diary (see below) or actigraphy. In addition to the sleep diary, the time of melatonin secretion or rhythm of core body temperature has been measured in some patients enrolled in the study, confirming the endogenous generation of non-24-hour circadian rhythms.

Blind

This disorder can be considered very likely in people who are completely blind with periodic and daytime sleepiness, although other causes for this common symptom need to be ruled out. In the setting of the study, the diagnosis can be confirmed, and the length of the circadian cycle that can walk freely can be ascertained, with periodic assessment of circadian rhythms, such as the rhythm of core body temperature, melatonin secretion time, or by analyzing sleep-wake schedule patterns using actigraphy. Recent studies have used serial measurements of melatonin metabolites in urine concentrations or melatonin in saliva. This test is currently not available for routine clinical use.

Classification

Since 1979, this disorder has been recognized by the American Academy of Sleep Medicine:

- Diagnostic Classification of Sleep Disorders and Passion (DCSAD), 1979: Non-24-Hour Sleep Syndrome; C.2.d code

- International Classification of Sleep Disorders , 1 & amp; Eds revised. (ICSD), 1990, 1997: Non-24-Hour Sleep-Wake Syndrome (or Non-Hour Sleep Disorder 24); code 780.55-2

- International Classification of Sleep Disorders , second edition. (ICSD-2), 2005: Non-24-Hour Sleep Syndrome Sleep (Alternatively, Sleeplessness-Build Without 24 Hours); code 780.55-2

Since 2005, the disorder has been known under the name of the National Center for Health Statistics of the US and the US Medicare and Medicaid Services Centers in the adaptation and extension of the International Statistical Classification of Their Related Illnesses and Health Problems (ICD):

- ICD-9-CM: Sleep disordered circadian rhythm, type of free running; code 327.34 became effective in October 2005. Before the introduction of this code, nonspecific code 307.45, sleep disturbance of non-inorganic origin circadian rhythms, was available, and by 2014 remained the code recommended by DSM-5.

- ICD-10-CM: Sleep disorders circadian rhythm, type of free run; the G47.24 code will take effect from October 1, 2014.

Since 2013, this disorder has been recognized by the American Psychiatric Association:

- DSM-5, 2013: sleep-wake disorder circadian rhythms, Non-24-hour sleep-up type; ICD-9-CM Code 307.45 is recommended (no 327.34 acknowledgments are made), and ICD-10-CM G47.24 code is recommended when applicable.

Treatment

Sighted

Enforcing a 24-hour sleep-up schedule using an alarm clock or family intervention is often attempted but is usually unsuccessful. Exposure to bright light upon awakening to combat the tendency of circadian rhythms to be delayed, similar to treatment for delayed sleep phase disorder, and seasonal affective disorder (SAD) has been found to be effective in some cases, as does melatonin at the subjective end of the day or night. Light therapy involves at least 20 minutes exposure to light intensity of 3000 to 10000 lux. Going out on a sunny day can achieve the same benefits as a special lamp (light box). Bright light therapy combined with the use of melatonin as chronobiotic and light before bedtime avoidance can be the most effective treatment. The administration of melatonin shifts the circadian rhythm according to the phase response curve (PRC) which is essentially the reverse of the PRC light. When taken in the afternoon or evening, it resets the previous clock; when taken in the morning, it shifts hours later. Therefore, the success of entrainment depends on the timing of proper administration of melatonin. The accuracy required to successfully manage melatonin administration time requires a trial and error period, as well as dosage. In addition to natural fluctuations in circadian rhythms, seasonal changes including temperature, daylight hours, light intensity and diet tend to affect the effectiveness of melatonin and light therapy because these exogenous zeitgebers will compete for hormonal homoeostasis. Further to this there is an unexpected disruption to compete even when a stable cycle is reached; such as travel, sports, stress, alcohol, or even the use of light-emitting technology close to a subjective night/night.

Hypnotics and/or stimulants (to promote sleep and awake, respectively) are sometimes used. Usually a sleep diary is required to assist in the evaluation of care, although the advent of modern actigraphic devices can also be helpful in logging sleep data. In addition, graphics can now be created using mobile apps, using the built-in accelerometer on most smartphones currently in use. Charts and diary notes can be shared with your doctor. However, due to their lack of clinical accuracy should not be used for diagnosis, but to monitor the cycle and general progress of each drug used.

Blind

In the 1980s and 1990s, several melatonin administration trials for completely blind individuals without light perception resulted in improvements in sleep patterns, but it was not clear at the time if the benefit was due to the entrainment of the light cues. Then, using endogenous melatonin as a marker for circadian rhythms, several research groups showed that timely administration of melatonin could train a free-running rhythm in total blind people. For example, Sack et al. found that 6 of 7 patients treated with 10 mg of melatonin at bedtime were usually included. When the dose is gradually reduced to 0.5 mg in three subjects, entrainment persists. Furthermore, it was shown that the treatment started with 0.5 mg dose of entrainment. One subject that failed to use a higher dose was successfully inserted at a lower dose. Low doses produce melatonin blood levels similar to the natural concentrations produced by night pineal secretions.

Products containing melatonin are available as dietary supplements in the United States and Canada, available on the table. This "supplement" does not require FDA approval. Because prescription drugs can be prescribed from the label, treatment recommendations for people who do not smoke at 24 hours may vary.

There has been a constant growth in the field of melatonin and melatonin receptor agonists since the 1980s. In 2005 Ramelteon (Rozerem Ã, ® ) was the first approved melatonin agonist in the United States (US), indicated for the treatment of insomnia in adults. Melatonin in the form of prolonged release (trade name Circadin ® ) was approved in 2007 in Europe (EU) for use as short-term treatment, in patients 55 years and older, for primary insomnia. Tasimelteon (trade name Hetlioz Ã,® ) received FDA approval in January 2014 for people diagnosed with non-24. TIK-301 (Tikvah Therapeutics, Atlanta, USA) has been in phase II clinical trials in the United States since 2002 and the FDA gave it the orophane drug set-up in May 2004 for use as a treatment for circadian rhythm sleep disorders in blind individuals without light perception as well individuals with tardive dyskinesia.

Prevalence

There are about 140,000 people with N24 - both visible and blind - in the EU, a total prevalence of about 3 per 10,000, or 0.03%. It is unknown how many individuals with this disorder do not seek medical attention, so the incidence may be higher. The European portal for rare disease, Orphanet, lists Non-24 as a rare disease by definition: less than 1 person is affected for every 2,000 population. The US National Organization for Rare Disorders (NORD) lists Non-24 as a rare disease by definition.

Sighted

In 2005, there were fewer than 100 cases of people seen with non-24s reported in the scientific literature.

Blind

While both visually and blind people are diagnosed with non-24, the disorder is believed to affect individuals who are more blind than those seen. It is estimated by researchers that of the 1.3 million blind people in the US, 10% have no perception of light at all. Of the group, it is estimated that about half to three quarters, or 65,000 to 95,000 Americans, suffer from non-24s.

History

Melatonin's administration capability to train the free-running rhythm was first demonstrated by Redman et al. in 1983 in mice maintained in a time-free environment.

Sighted

The first report and the non-24 case description, a man living on 26 hours a day, is "A man who takes too long a day" by Ann L. Eliott et al. in November 1970. The delayed sleep phase disorder was related and more commonly not described until 1981.

Blind

In the first non-24 detailed study in blind subjects, researchers reported in 28-year-old men who had a 24.9 hour rhythm in sleep, plasma cortisol, and other parameters. Even while following a typical 24-hour schedule for bedtime, wake-up time, work, and eating, the rhythm of the male body continues to shift.

Direction of research

Not all individuals who are completely blind have free-running rhythms, and those who often show relative coordination as their endogenous rhythm approach the normal time. It has been suggested that there are non-photic time signals that are important to maintain entrainment, but these cues are still waiting to be characterized.

See also

- Pending phase delay

- Advanced sleep phase breakdown

- Irregular sleep-wake rhythm

- Sleep disordered circadian rhythm

- Seasonal affective disorder (SAD)

References

Further reading

- DeRoshia, Charles W.; Colletti, Laura C.; Mallis, Melissa M. (2008). "The Influence of Mars Exploration Rovers (MER) Radar Schedule on Locomotor Circadian Rhythms, Sleep and Fatigue" (PDF 10.85MB) Activities . NASA Ames Research Center. NASA/TM-2008-214560.

External links

Source of the article : Wikipedia